The Albigensian Crusade: A War of Faith and Power in the South of France

In the medieval West, religion and society are one and the Catholic Church is omnipresent. From the 11th century, the Church established itself as an autonomous institution. The popes initiated a series of reforms aimed at asserting their omnipotence (concept of papal theocracy), unifying the Church and seeking to control the whole of society, including princes. The historians named it the Gregorian Reform. In this context, any community escaping the control of ecclesiastical authority became suspect.

Since the 11th century, the Roman Catholic Church sought to extend its influence over the South of France. It clashed with the great Occitan lords who had placed members of their family at the head of the clergy and contested the interference of the pope. The accusation of heresy was regularly made by the Church as a real instrument of political destabilization.

The Great Southern War (12th century)

Also known as the Southern Hundred Years’ War, it involved the Counts of Toulouse against the Counts of Barcelona (Kings of Aragon from 1137), their vassals (first and foremost the Viscounts Trencavel), and their neighbours, in particular the Dukes of Aquitaine (Kings of England after 1152), the Emperors of the Holy Roman Empire and, above all, the Kings of France from the middle of the 12th century. It overlapped with other conflicts, between the Counts of Poitiers and Dukes of Aquitaine and the Counts of Toulouse, or the conflict between the Capetians and Plantagenets which opposed the kings of France against their vassals in France, but also monarchs of England.

Begun in 1098 with the capture of Toulouse by Duke Guillaume IX of Aquitaine – grandfather of Aliénor and often considered the first troubadour (Occitan poet), the Great Southern War ended in 1196 with the marriage of the Count of Toulouse to Joan of England, while the Cathar question became more present. This war has sometimes been considered the main cause of the failure to form a unified Occitan state, which would have been able to resist the Albigensian Crusade and the Capetian domination in the 13th century.

Political situation in the south of France circa 1030

During this period, the princes and lords of the Midi (south of France) regularly accused each other of heresy. In 1145, the Count of Toulouse Alphonse de Jourdain targeted Roger I Trencavel, Viscount of Albi and Carcassonne. He urged the Cistercian Bernard of Clairvaux (today Saint Bernard) to launch a preaching mission in Albi, hence the name “Albigeois” sometimes given to Occitan ‘heretics’. At the Council of Tours in 1163, the debates were dominated by a great rival of the Count of Toulouse, Henry II Plantagenet, King of England and Duke of Aquitaine. The city of Toulouse was singled out as being ‘infested’ by heresy. In 1177, the Count of Toulouse Raymond V sought to have Roger II Trencavel designated as the main troublemaker: he made a direct appeal to the King of France, then Louis VII, and the Church to intervene against the ‘heretics’. The Great Southern War ended but the ambition of Pope Innocent III remained to organize a centralised Church under his absolute authority.

At the beginning of the 12th century, heavy black clouds gather over the vast County of Toulouse. In 1208, Pierre de Castelnau, the papal legate, is assassinated in Saint-Gilles, on the lands of the Count of Toulouse, after an interview with the latter. The Count is accused (even though his responsibility was never proven), and Innocent III takes his pretext to launch a call for a crusade against the ‘Albigensians’, the first crusade to be conducted in Christian territory.

Chronology of the Albigensian Crusade 1209-1229

The Crusaders gather in Avignon in the summer of 1209 and their first target is the town of Béziers, on the land of the Viscount Trencavel. Despite strong fortifications, the city falls on the first day and part of the population is slaughtered. The leader of the crusade, Arnaud Amaury, papal legate and abbot of Cîteaux, is said to have declared “Kill them all! God will recognize his own“. Carcassonne falls soon after, followed by several towns of the Lauragais area, during the summer-autumn of 1209. Simon de Monfort, Lord of Monfort (near Paris) and Earl of Leicester in England, is designated as the chief of the crusade.

View of the medieval Cité de Carcassonne

The first stake of this crusade is lit at Minerve in 1210 where more than 100 people accused of heresy are killed. The crusaders are moving ever closer to Toulouse. The Count is excommunicated in April 1211 and Simon is now free to start the conquest of the county. Toulouse is besieged for the first time in June 1211, but the crusaders fail to take the city. The conflict stabilises and Simon de Monfort starts organising his new territory from the town of Pamiers, 70km south of Toulouse.

In January 1213, Peter II of Aragon receives the homage of Raimond VI and places all the territories threatened by the crusaders under his protection. This episode is of the utmost importance as the south of France now escapes the suzerainty of the King of France. Pere el Catòlic is an important figure of Christianity, having defeated the Almohads at Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. Unfortunately for Toulouse, Peter is killed at the battle of Muret in September. Raimond leaves his county, seeking for support in England and Provence, and meeting with the Pope in Rome. However, at the Lateran Council of November 1215, the Pope recognises the conquest of Toulouse, and the king confirms Simon’s rights on the county early 1216.

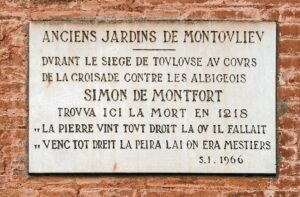

The Count of Toulouse is dispossessed of his land except for the Marquisate of Provence. From Avignon, Raimond VI leaves for Aragon to gather troops while his son, the future Raimond VII marches on the rich city of Beaucaire, by the Rhône River. Simon de Monfort besieges the town without success. During his absence Toulouse welcomes the return of the Count Raimond VI. Simon is forced to return to Toulouse and the second siege of the city starts in September 1217; it will last ten months. On the 25 of June, Simon de Monfort is killed by a projectile and his son Amaury lifts the siege one month later. A plaque still stands on the walls of the Jardin des Plantes in Toulouse where he was killed. It states: “Venc tot dreit la peira lai on era mestiers” (‘The stone came straight to where it was needed’); these are the words written in the Canso, a testimony of the enduring affection of the local people for this northern lord.

Left: Plaque at Jardin des Plantes, Toulouse. Right : La mort de Simon de Montfort, engraving by Alphonse de Neuville

The Lion Takes the Cross: The time of the King

The prince Louis, future Louis VIII, joins the crusade in 1219 and, after the slaughter of the population in Marmande, besieges Toulouse in June of the same year; the city resists a third siege and, 45 days later, the king returns to Paris. This opens a period of victories for the Count of Toulouse who regains part of the lost territories. Both parties appeal to King Philippe Auguste to find a way out, but the monarch only offers his neutrality. Lacking resources and troops, Amaury de Monfort, son of Simon, offers a truce in January 1224 and leaves the Midi, ceding all his territories to the new King of France, Louis VIII. Contrary to his father, Louis is ready to impose his direct authority in the south.

Raimond VII is again excommunicated in 1226, offering a good pretext to the king for a new campaign. Louis VII subdues the south but dies in Auvergne in November on his journey back to Paris. The royal power, now under Louis IX (Saint Louis) maintain its pressure on the Midi and, after more than 20 years of war, and facing the fatigue of the population, several local lords submit to the king.

Twenty years of war forces Count Raimond VII to open negotiations. After receiving the pardon of the Church on the forecourt of Notre-Dame de Paris, he submits in April 1229 to Queen Blanche of Castile, her son the young King Louis IX, and the representative of the Pope. By the Treaty of Paris, Raimond VII retains his title of Count of Toulouse but loses part of his territories. In addition, he gives in marriage his only heiress, Jeanne, to one of the king’s brothers.

L’Agitateur du Languedoc by Jean-Paul Laurens 1887

With the end of the crusade and the establishment of the Inquisition, the fight against heresy enters a judicial phase. In 1235, faced with the harshness of the investigations and sentences, Toulouse rebels and chases the Dominicans. Raimond Trencavel, heir to the viscounty of Carcassonne and Béziers, rebels against the King of France in 1240, without success. Resistance to the inquisitorial mission reaches a point of no return with the ‘Avignonet affair’: in May 1242, two inquisitors and their companions are assassinated by men-at-arms from Montségur, perhaps at the instigation of the Count of Toulouse. This is the signal for the uprising and Raimond VII openly opposes the King of France. However, the attempt fails, and the great lords of the south are forced to submit to the royal power. The Count of Toulouse abandons any desire for revolt.

Château of Montségur in Ariège, Pyrénées – so called ‘Château Cathare’

When Raimond VII dies in September 1249, the husband of his daughter Jeanne becomes Count of Toulouse in her name. Alphonse, Count of Poitiers and Saintonge, brother of the King of France, did not reside in Toulouse and his southern domains were administered remotely. In 1270, Alphonse decides to participate in the crusader expedition to Tunis, accompanied by his wife. The operation is a failure; the King Louis IX (Saint Louis) dies in Tunis, Alphonse on the way back, followed a few days later by Jeanne. The couple has no children, and the County of Toulouse is absorbed into the royal domain of the new Capetian sovereign Philippe III (called ‘le Hardi’ meaning ‘the Bold’).

Under the impetus of the Inquisition, the fight against ‘heretics’ will continue for a few decades. Guilhèm Belibasta, said to be the last Cathar, is burnt at the stake in 1321.

Heretics in Languedoc; Catharism: Myths and Reality

In its traditional definition, ‘Catharism’ is presented as a religious movement in its own right. Appearing in the 12th century, it would have spread from the Rhine Valley to northern Italy, as far as the south of France. The ‘Cathars’ would have formed a real Church, itself organized into regional churches, the community would including simple believers and ordained ‘heretics’. The latter would practice rituals such as the consolament (sacrament of ordination or extreme unction by laying on of hands) and would sometimes bear the titles of bishops or deacons.

Château of Peyrepertuse, Aude – another ‘Château Cathare’

For the medieval Catholic Church, these so-called heretics were no different from those condemned by the Fathers of the Church during Late Antiquity. Learned clerics of the 12th and 13th centuries thus replicated earlier anti-heretical texts to combat dissent, inaccurately projecting a pre-existing narrative onto the heretics of Occitanie. This narrative portrayed them as a counter-church originating in the East, mirroring the Manicheans described by Saint Augustine. Their beliefs were falsely characterized as dualistic, attributing the creation of spirit to God and the creation of matter (and thus the Earth) to the Devil.

Archbishop Palace of La Berbie in Albi; at the back the Cathédrale Sainte-Cécile

For some historians, ‘Catharism’ constituted a particular form of Christianity, propagated on a European scale, based on an original doctrine that textual sources allow to be reconstructed. For others, this vast ‘Cathar’ movement never existed as such: historiography simply constructed a unified heresy by lending the same name, the same practices and the same beliefs to dissident groups that were in reality very different. The idea of a true heretical ‘counter-Church’ has also been entertained by the Catholic Church itself since Antiquity. Sometimes used as a threat weighing on society, it served as a convenient pretext to repress all dissident voices.

A majority among historians supports the second interpretation today, but the debates, touching on regional identity, are still lively. The suffering of the population was real, though, and the integration of the County of Toulouse into the royal domain marked an important step toward the domination of the territory of France by the Capetian dynasty.

Explore southwest France and discover the unique history of the Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, visiting Toulouse, Carcassonne and Albi, on our tour Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne.

- View Tours Romain is currently leading

- Watch his short video introducing the ‘Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne’ tour

View our current selection of programs to France

Article images

Cité de Carcassonne. Entrance of the Count’s castle ID 29727240 © Milesfoto | Dreamstime.com

Political situation in the south of France circa 1030 by Nicolas Eynaud, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

View of Carcassonne ID 76132066 © Thomas Lenne | Dreamstime.com

Entrée Virebent du Jardin des Plantes de Toulouse by Didier Descouens, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Death of Simon de Montfort at the siege of Toulouse (25 June 1218) by Alphonse de Neuville, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

L’Agitateur du Languedoc by Jean-Paul Laurens 1887, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Château de Montségur ID 42363516 © Makaryioanov | Dreamstime.com

Château of Peyrepertuse, Aude ID 233260071 © Bidouze Stephane | Dreamstime.com

The Episcopal City of Albi: The Palais de la Berbie and the Albi Cathedral, seen from the right bank of the Tarn river by Didier Descouens CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

These images have been resized for this website.

Sources

Cathares, Toulouse dans la Croisade. Musée Saint-Raymond, Musée d’Archéologie de Toulouse

Laurent Macé, “Hérétiques”! Les Toulousains dans la croisade (1209-1229), Editions Cairn, Morlaas, April 2024

Chanson de la Croisade Albigeoise, Editions Les Belles Lettres, Paris, June 2018

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2025

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2025  Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2026

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2026